2 Small town neighborhood

We lived in an old, two-story house on Oak Street, surrounded by a diverse mix of neighbors, many of them families with children my age. Our next door neighbor was a postman with two children a bit older than us, including a teenage daughter who occasionally babysat. We had a few elderly widows, including Mrs. Demert, who wrapped her tiny Chihuahua puppy into a snug hand-knit body suit before his daily walks in the cold Wisconsin winters. There was Mrs. Fry, who lived alone except during the summer months when I saw my first taste of California, a license plate on a car parked in front of her house that carried a load of grandchildren. We had the Carters, a family of Sixties-era hippies, who apparently used drugs enough that my mother used their name as a superlative: “…more X than Carters have pills.”

We knew everyone: lawyers, doctors, schoolteachers, the town barber and his kids, a fireman and his family, small business owners including the grocery store, hardware store, a furniture store, and much more. And while of course there were differences in wealth among all of us, we all lived in similar-sized houses and the children attended the same schools.

Well, most of us did. Even a small town like Neillsville had private parochial elementary schools: St. Mary’s Catholic, and St. John’s Lutheran, Bible Baptist. But any educational differences had to do only with religion, which to outsiders would have seemed tediously arcane among Christian people who agree on far more than they disagree. We didn’t know there could be secular private schools for wealthy kids, or even specialized schools for people whose parents had enough money to pay to have kids focus on, say, the arts, or to get an education surrounded by other rich kids. We just didn’t know that world existed.

Politically, as can be expected from a small Midwestern town, most people seemed sympathetic to the Republican Party, but it was by no means a shut-out, in the way that Democrats exclusively dominate urban areas or university campuses in the rest of America. You would not draw attention to yourself by having it be known publicly that were a Republican in my small town – any more than anyone would think you were extreme for being a Democrat – but you would be better off keeping your views mostly to yourself, because you couldn’t assume that the others around you would agree with you.

The US Supreme Court ruling that prohibited prayer in classrooms was only a decade or so old by the time I was in school, so although we didn’t overtly pray (I’m not sure in Neillsville the schools ever did) it certainly wouldn’t have been the kind of thing parents would have complained about. My kindergarten teacher led us to say grace before our snack time, though it’s likely that she did this because most of the kids said grace at home, and it would have been completely natural to pray at school too.

My friends included people like Roberta, the girl who seemed perpetually happy. Or Roger, the big-boned farm boy who, like many others in our class, always smelled of freshly-milked cows.

I knew that my family was poorer than some families – and better-off than others – but at the time it seemed less about money than about priorities. Some of the houses boasted prettier, well-manicured lawns, but we had a bigger backyard garden. Some people had nicer furniture and carpeting, bigger TV sets or newer cars. But nothing about any of their lifestyles seemed beyond the reach of my own family. Occasionally we’d hear about somebody going on a big vacation, maybe by airplane to a faraway tropical island, and that seemed like the peak of luxury, but my family went on vacations too. Maybe we didn’t travel by airplane or stay in fancy or expensive hotels, but we could go where we wanted. Who needs money when you can stay with relatives or camped in a tent along the way, eating sandwiches and canned food.

At school, the differences in wealth or prestige didn’t matter a bit. The “rich kids”, children of lawyers and doctors, ate the same school lunch that we did. If they brought their own, it might have come in a fancier cartoon-labeled lunchbox while mine was a paper sack, but the contents were the same. A tiny handful of kids were rumored to have subsidized or free lunch. These were invariably victims of tragedy: the family whose home had been destroyed by fire, the kids whose father died in a boat accident, or the big family outside town who parents didn’t seem to be normal (maybe they were mentally handicapped?). Even then, to be on some type of public assistance was something everyone –including the recipients – viewed as disastrous, a shameful hardship for all involved and definitely just a temporary stepping stone on the way to self-sufficiency.

If there was a correlation between family status and school performance, it wasn’t a strong one. With few exceptions, everyone came from intact families – a father and mother – and the family attitude toward education probably affected school results as much as anything. When I discovered early in first grade that I tended to do well in school compared to the rest of the class, I found that my chief competitors were the children of schoolteachers or those whose parents had been to college. Even then, any link to the parents seemed tenuous, because I could always find exceptions, and of course academic performance was only one of many ways to measure the students. Some were better athletes or artists, some were more social. But we all attended the same school, and learned the same things.

The Neillsville Public Schools were located on a single tract of land on the east side of town, eventually consolidated into a single building. You entered the east doors for Kindergarten and graduated out of the west doors for high school. We had roughly 100 kids in each grade, split among four or five teachers. A small administrative staff rounded out the school with dedicated art and music teachers in elementary school, and more specialized teachers in high school. Although the place seemed huge to me at the time, the faculty – especially the longer-served ones – knew pretty much every student, if not directly then from teaching siblings.

Our religion dominated our lives so much that I don’t remember many friends from elementary school who didn’t have a connection to church, but we had neighbors, and like all kids I suppose it was only natural to find ways to play with them.

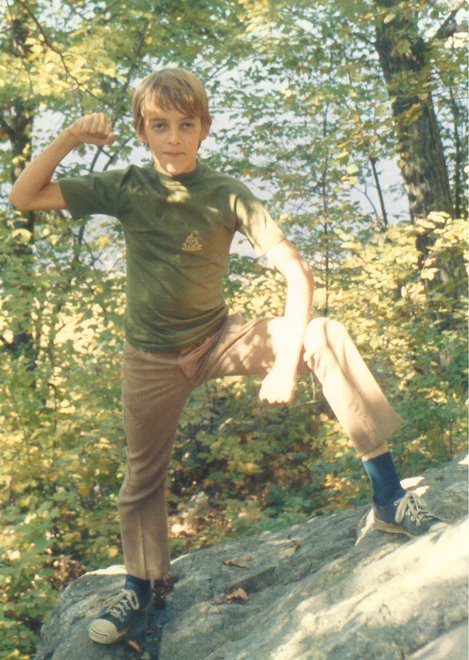

Although technically we lived in a city (the largest, the capitol city, of Clark County!), our neighborhood (like every neighborhood, come to think of it) was on the outskirts of town. An elderly philanthropist, Kurt Listeman, had donated some land to the city long ago as an arboretum, a large undeveloped forest with some trails carved into it, running along a scenic path to the nearby Black River. It wasn’t the kind of place that today I’d call a “hiking trail”, but to our pre-teen minds, it was the ideal place for play, especially on endless summer days in a world before parents thought to overschedule their children in “day camps”. Everything we did, we had to invent for ourselves.

In the large, overgrown field that separated our backyard from the arboretum, we found plenty of other neighborhood children who had come to play, and in time we invented a game we called “all day game”. If you showed up sometime in the morning, you’d find children from throughout the neighborhood, usually divided into teams of some sort, all playing an elaborate version of hide-and-seek. We imagined that the other neighbors were from a hostile foreign country, or that we were spies sent to penetrate the defenses of the enemy, or that they were invaders intent on destroying us. We rarely came face-to-face with the enemy; we usually only saw them from a distance.

Occasionally one side would spot the other at a sufficient distance to plan a surprise “attack”, creeping slowly through the underbrush just to the point of the other camp, sticks and stones in hand, ready to deliver a beating. Inevitably, the opposing side would discover the attack just in time either to flee or to counter-attack, depending on the whim of the players. The counter-attack, of course, would result in reverse behavior: once a side discovered it was about to be raided, they would themselves need to flee or counter-counter the attack, depending on the circumstances, precipitating even more fun of the chase.

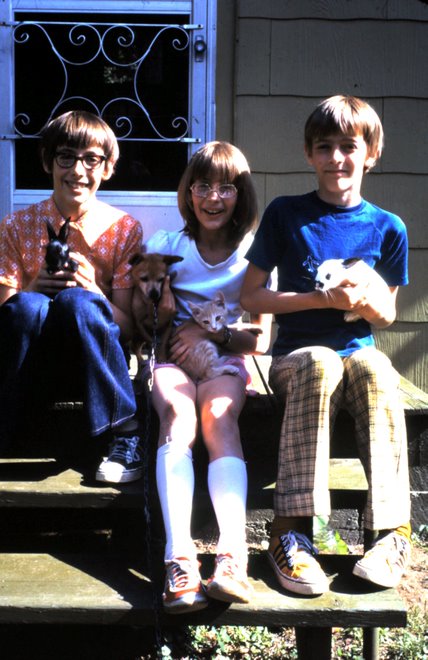

These games really did last all day, and everyone in the neighborhood seemed to join. Usually it was my family—both brother and sister – plus the Gungors, the Shorts, the Frys, and many others. The kids who we didn’t know from church, we knew from school – or if they were in different classes, we at least knew of them – so it was easy to identify our “enemies” by name.

Part of being away from home, running through the woods, all day was that obviously our parents (i.e. mothers – the mothers were all stay-at-home) wouldn’t be watching us. Nowadays such inattention would be unthinkable: what responsible parent wouldn’t know exactly where a pre-teen child is? But our mothers interpreted our absence as a sign we were happy and self-sufficient. They knew we’d be home eventually, if not for treatment of the occasional scrape or bruise, then certainly in time for dinner. My mother’s only rule, at least until we were older, was that we were not to go near the river itself. She knew too many personal examples of children who had drowned. In fact, one boy in our neighborhood did drown, and we knew of at least one other kid at school who unsuccessfully tried to rescue his younger brother who had fallen in during the springtime. So we stayed away from the river. But the rest of the woods was fair game and we took full advantage of it.

On one particular day, during an especially long forage into the woods, I remember we stumbled upon a group of much older teenagers hiding an illicit stash of beer, cigarettes, and who knows what else. At first were afraid they might try to hurt us for having discovered their evil den of sin, but the beer had apparently put them in a happy mood, so instead they just laughed at us.

Otherwise mostly what we found in the woods were trees (good for building forts and hideouts), sticks (good for make-shift weapons), and the occasional baby bird or animal (good for bringing home as an adopted pet). It was endless, nonstop adventure.